|

The quality of the beef cuts consumers buy in the store starts many months before on the ranch or farm.

Preset protocols established in the veterinarian-producer relationship include a vaccination schedule. Ranchers watch over their herds and can detect when a calf or cow are “off” and need extra medical attention. Using clinical parameters, such as temperature, heart rate, and other tests, they can call the vet and work within their medication protocols to treat these animals in a timely and effective manner. This may include giving medication or keeping cows isolated from the herd. Moving cattle with low-stress handling techniques produces better quality beef. While movies depict cowboys and cattle in raging stampedes or wild bucking bulls, or using electric cattle prods to shock the cattle, this is not how they are actually raised. Low-stress handling and slow moving cows wouldn’t sell movie tickets. Keeping an animal frightened and running doesn’t make happy cows; it makes scared skinny cattle that are flighty, nervous, prone to illness, and poor cuts of meat called “dark cutters” that cannot be sold at the grocery store. No one benefits from cattle mistreatment. Food safety inspection requirements at the packing plant require animals are healthy at harvesting time, and the meat is tested for medication residues to protect consumers. Every type of medication from vaccines to antibiotics produced by pharmaceutical companies has a timetable for residues, which is the time it will take for that medication to leave the animal’s system completely. Food safety also looks for quality in the meat cuts, all of which point to proper handling, and is part of the responsibility of the producer. Keeping good histories of herd activity, medical records, and following the vaccine schedule allows the producer to ship cattle to the feedlot for finishing or to the packing plant for processing knowing that there are no medication residues in the meat and that there will be no “dark cutters.” Dark cutters is an industry term for meat that is dark from lactic acid release during stressful events and fails to achieve that red color that consumers see at the store. Proper care and handling are the responsibility of the producer. Many farmers and ranchers participate in the beef quality assurance program, which is a voluntary program to educate producers on all aspects of proper beef production. There are state BQA coordinators and a national office that offer workshops and certification to individuals and groups. The BQA program’s goals include education of producers and increasing consumer confidence that the beef they buy at market is humanely produced and high quality meat. Watch a series of BQA videos that educate producers on a variety of topics.

1 Comment

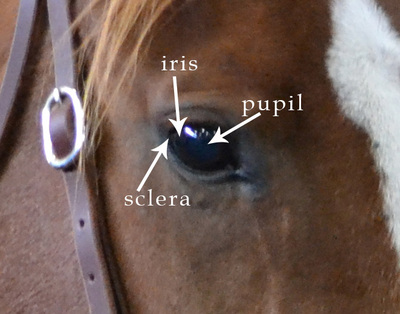

When light falls across an animal at night, the eerie glow that peers back at you from the dark can be disconcerting.

The very reason that animals produce this glow and people do not is what allows them to see so well in the dark. This eye-shine is made of light reflected back from a layer of cells that lie below the retina at the back of the eye. In horses and other animals, this layer of cells is called the tapetum. It covers the upper half of the ocular fundis, which is the back curvature of the inner eye. It gives the light a second chance to hit the cones and rods that it missed in its first pass across the retina. This increased light exposure is the key to low light vision. The next time you see eyes shining in the dark, from a pet, a horse, or wild animal; just remember that you’re seeing light reflected from a single layer of cells. Watch a video of a horse eye exam here. The steady chatter of whinnies, nickers, and snorts across the aisles by the young horses stalled in the Adams-Atkinson barn at Colorado State University filled the air and drowned out the conversations of interested buyers.

The 17th annual Kesa Quarter Horse sale featured 56 catalog entries. The horses ranged from weanlings born during the spring and summer to geldings, mares, and stallions from their breeding program. Hip number eight, Speedywood Jo Jo a 2009 bay stallion, was the top selling horse bringing $14,500. Trained by Luke Jones of Iowa, Speedywood Jo Jo has already qualified for the 2014 AQHA World Show. There were many different reasons for bidders to raise their card as the auctioneer chanted the current price for each horse in the ring; a desire to train the next champion from the ground up, acquiring a horse that already had competition earnings and points, or adding proven bloodlines into their breeding program. Dr. Patrick McCue, CSU professor and equine assisted reproductive specialist, lectured on special reproductive cases in stallions and mares during the break between the preview and sale. One example highlighted the successful fertilization of eggs harvested from a mare that had died. A short video clip of the manual injection of a sperm into an egg with a pipette under a microscope captured attendees’ full attention. Ken Matzner and Sam Shoultz, owners of Kesa Quarter Horses, have been long-time partners with CSU’s equine sciences program. One way they support the education of the students is by providing internship opportunities at their facility east of Fort Collins. Dana Ratcliffe, a junior equine science major, worked with the weanlings as part of her summer internship. “Working at Kesa was a great life experience,” Ratcliffe said. “I learned the proper way to halter break babies and how to handle studs.” Sarah Domagala attended the sale as part of an assignment from the colt training class and explained what she would look for if she were buying a weanling. “I look at personality because it’s something they’re going to bring through their entire lives,” Domagala said. “So I look at that. It’s kind of hard to judge [their] body at this age since they’re always changing.” The vesicular stomatitis virus outbreak this summer, and subsequent quarantine of all horses to their home barns by the state veterinarian, pushed Kesa’s annual sale from August to October. However, this delay gave Erin Ramirez, a senior in the equine program, the opportunity to work with the weanlings this fall. “We would bring them in with their mothers from pasture, and then drive them into smaller pens and separate them out,” Ramirez said. “We would work on getting halters on them.” With the sale papers completed, the only sounds left in the barn were the shuffling of papers, phone calls arranging transport, and the rhythmic clip-clop of the last weanlings being led down the aisles to waiting trailers. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed